Last year, I started taking improv classes at Boom Chicago to become a better facilitator. I reckoned I'd score some warm up games and icebreakers and maybe get a bit better at rolling with things. What I got was bit by the improv bug. I started listening to improv podcasts, reading improv books, going to shows, learning the lore and legends of Boom and Second City. My Level 1 classmates and I bonded, graduated to Level 2, and when we couldn't all take Level 3 together, put together enough people to get a class added. We're a troupe - we belong together.

It's no coincidence that this feels exactly like the bond I felt with fellow activists. OK, maybe the stakes are slightly different when you're walking onto a nuclear weapons test site or heading into a storm at sea. But get up onto a cold stage, in front of an audience that’s invisible behind the lights, with a group of people that are being asked to make strangers laugh, and you are taking risks. You want to know you can trust your companions, and that you have each others' backs. Pancake landing or triumphant thunder, you always want to be able to look each other in the eye.

For years before I got up on that stage, I've been aware that activism has a lot to learn from improv. When the HR department at Greenpeace announced that our annual day out would include improv training back in the early oughts, I was dubious I was going to learn anything useful. To this day I'm not entirely sure, but I believe it may have been Brendan Hunt (of Ted Lasso fame) who taught us "Yes, And." It started with a scold: activists were all about saying "No" and "Stop" and "That Sucks." Fine, maybe that's your job out there. But when you bring that energy into a creative brainstorm, you kill flow, you dampen people's courage to share, you never hear the half-baked idea that might bake up into a perfect soufflé. You need to build on each other's ideas rather than cancel them.

When Tommy Crawford and I founded Dancing Fox, improv was already in our DNA thanks in large part to Lucy Taylor, who introduced us to the thinking of Keith Johnstone and the improv mantra of "Let Go, Notice More, Use Everything." I mean look at that. If you've ever been a part of a social change campaign that you're trying to shoulder into the mainstream from the fringe, what better advice could there be?

The best campaigners hold their plans and assumptions lightly, ready at anytime to nimbly shift to something more effective. They let go.

The best campaigners listen to the data, listen to the audience, listen to the wind, and grip onto whatever's got juice. They notice more.

The best campaigners don't need massive budgets or the latest tech if they're good at guerilla and versed in viral. They use everything.

When I think about the campaigns that really worked at Greenpeace, every one of them had some aspect of good improv. Keith Johnstone's improv advice is pretty good life advice: "Treat everything as a gift." Your improv partner's shoe is untied? That's a gift. An audience member heckles you? That's a gift.

Reddit trolls decide to try and turn your Humpback whale naming competition into a farce by running up votes for “Mister Splashy Pants?” Now there was a freaking gift. There are humpbacks swimming free in the Pacific today who may just owe their lives to the embrace that got from my social media team, rolling with it and turning it into what advertising guru Russel Davies called "one of the defining moments in New Media marketing."

As horrible as it was, the Exxon Valdez oil spill was also, in its way, a gift. Kelly Rigg and the team working to protect the Antarctic from oil and gas exploration pivoted from asking people to imagine what an oil spill might look like in the Antarctic to pointing to an example of exactly how bad a spill could be in a far less challenging environment. It was the turning point that got Jacques Cousteau whispering in the ear of the French government, and turning a "never gonna happen," Overton-window setting measure to ban mineral and gas exploration for 50 years into International law.

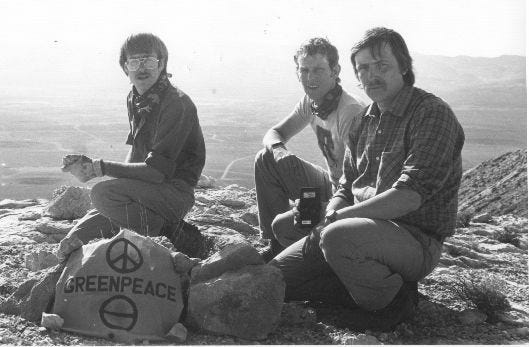

My own ass may have been saved by a stunning bit of improv from Steve Rohl, a local Las Vegas activist who helped mastermind the incursion four of us made into the Nevada nuclear weapons test site in 1983 to stop, with our presence near ground zero, an underground detonation. We hid in the desert for four days while helicopters and patrols combed the area. Our only lifeline of communications was a daily radio check-in with Steve at the nearest phone booth (remember phone booths?). Which happened to be in the parking lot of an isolated greasy-spoon diner on an empty highway where every test site employee stopped for their morning coffee on the way to work. Steve kind of stood out, with a backpack full of radio gear with a whip antenna extending high into the air. Two test site security guards approached and asked what he was up to. But Steve had hung around enough test site workers long enough to know that all he had to do was convincingly deliver one line to get out of hot water. And that line was "Do you have a need to know?" It was the pat phrase of someone with a higher security clearance signaling that classified information was involved. "Nope" was the response, and back they went to their eggs and bacon.

Thanks, Steve, for having our back, and for being good at improv.

"AA"! I totally get the improv/activism connection & I do applaud your deep dive into the wide-open unknown, because both endeavors are risky. I'm not sure that I have the courage (whether it's risking bombing on stage, or risking getting bombed in the Nevada desert). But, I'm glad you do! -"JTJ"